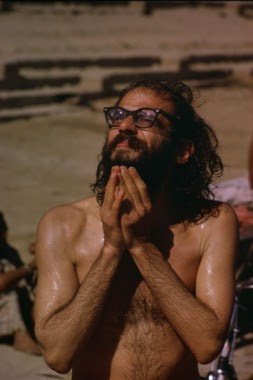

Allen Ginsberg and India : Ginsberg failed to understand India

Review of BBC 3 documentary: Ginsberg in India

From The Sunflower Collective

|

| Source: http://asiasociety.org/ |

Allen Ginsberg came to India for the first time in early sixties. These were important times for India; most importantly, its long standing dispute with China over Tibet and border areas reached a crescendo in the shape of a war in 1962. Ginsberg was in India when the war was on. However, his travelogue Indian Journals, which documented his time here barely mentioned the war which India lost miserably. (Within two years of the defeat, Pandit Nehru passed away; he and his defence minister V.K.Krishna Menon were heavily blamed for not being able to anticipate China’s aggressive designs. Both Nehru and Menon were considered leftists, the latter more so and their ideological orientation was cited by the critics as the prime reason behind their slip to identify the threat posed by China. The war with China divided the Indian Left also, with one faction of the Communist Party of India deciding to go its own way over the issue of support to the fellow communists on the other side of the Himalayas.)

The silence of a poet like Ginsberg on such matters,

whose poetry was always deeply and directly concerned with political

developments the world over, can only be called puzzling, to say the

least and any one going through Indian Journals is likely to be

intrigued by it.

The recent radio documentary by

Jeet Thayil, Booker nominated novelist and poet, looks into this and

other questions which continue to interest lovers of beat poetry and

literature in general. It deserves praise for at least looking into an

aspect of literary history that has largely been forgotten despite its

uniqueness and far-reaching consequences.

Take the matter of the Indo-China war. The

documentary has the writer Deborah Baker telling us that Ginsberg

believed India was turning into a “militaristic” state by warring with

China and that he wanted to go on a peace march with “Gandhians” to

protest this – her book A Blue Hand: Beats in India has more on this.

It can be safely said that Ginsberg’s views on India

becoming “militaristic” were either naïve or deliberately cruel. The

troubles with China had roots in the colonial period and were chiefly

concerned with its occupation of Tibet to which India objected, apart

from the delineation of the boundary between the two Asian giants. Dalai

Lama was given shelter by India after China invaded his country in an

act of naked imperialism, all the more ironic because the aggressor was a

communist country. To say that a country was turning “militaristic”

when involved in self-defense is utter baloney and even Gandhi would

have never agreed to it; one only needs to remember his support to

Britain and allies in Second World War to understand this simple point.

Poet and critic Ranjit Hoskote makes no bones in the same documentary about Ginsberg’s attitude towards India in general and terms it as an example of Orientalism. This is further illustrated by the Hungryalist poet Malay Roy Choudhury in the documentary. He mentions that Ginsberg only clicked beggars, lepers and the poor in India, at the exclusion of almost everything else. He narrates that his photographer father had admonished the Beat poet for the same, telling him: “whether a poet or a tourist, you white people are all the same.”

By choosing to look at India as being good only for a

certain kind of experience and refusing to consider that it was a

developing nation coming to terms with its own destiny – not willing to

stay encumbered by expectations of foreigners – Ginsberg is certainly

guilty of prima facie Orientalism.

It must be noted that Ginsberg also met with tantriks and bauls who are not traditionally upper-caste and it is not this author's intention to suggest that he was a dyed-in-the-wool Orientalist; rather, there were traces of Orientalism in his attitude.

His love for Benaras, a continually inhabited city,

which is how he described it in his last poem too, was a metaphor for

his love for the Indian civilization: a continuum existing as it was for

millennia, regardless of space and time. However, it was only an image

in Ginsberg’s mind when he came; his fault was to deliberately stick to

this image despite contrasting facts, and his sullen refusal to accept

the country in all its contradictions. For example, he did not once

mention in his book that the burning ghats which fascinated him so much

had a caste system of their own and Dalits could not be cremated at the

spots marked for the higher-castes.

It is entirely possible that Ginsberg was following

the foot-steps of the Transcendentalists, his literary fore-fathers

whose debt he always accepted but he did not question their attitudes

towards India. The Transcendentalists had also looked towards India for

spiritual guidance and glorified the Gita, a text which is abhorred by

India’s Dalits for its militaristic and reactionary philosophy that asks

people to leave everything in the hands of God and keep perpetuating

the system ad infinitum, regardless of the violence inherent in

Hinduism’s caste system. Had Ginsberg not heard that B.R. Ambedkar gave a

call for the annihilation of caste decades ago? Why was Ginsberg so

obsessed with Indian Sadhus and their mumbo-jumbo instead, who have,

through the centuries, acted as agents of perpetuating Hinduism along

with its pernicious caste system which has oppressed and enslaved

millions of people for so long?

There is also the slight matter of the Hungryalists.

In a lengthy interview to The Sunflower Collective recently, Malay RC

said quite categorically that Ginsberg spent close to two years with

Bengali poets, including the Hungryalists, whose manifestos he collected

and admired. According to Malay RC, it was only after coming in contact

with the Hungryalists that the Blake vision departed from Ginsberg, and

his poetry adopted a Bengali cadence, so to say, apart from imbibing

the Indian attitudes to life and its phenomena in general. The

documentary would have been enriched if the context to the Hungryalist

movement had been provided in greater detail and the links between Beats

and their Bengali counterparts (despite differences) looked into

further.

The documentary also cites poets like Adil Jussawalla

whom Ginsberg met while in Bombay. We can sense the annoyance Jussawala

must have felt with Ginsberg’s patronising attitude; with hardly any

inflection in his voice, he tells us that Ginsberg preferred the Urdu

poets to the English ones at a reading organised in Bombay and sat at

their feet “entranced” although he understood no Urdu.

All said and done, Ginsberg was a complex man. While his conscious being was that of a white tourist in India, he did allow his poetic sub-conscious to be open to India’s rich and varied influence.

He had an epiphany about his inclination towards Buddhism in India, leading to his subsequent conversion. (Ambedkar had also converted to Buddhism and maybe in this way, Ginsberg showed his aversion to Hinduism’s caste system.) The poetic influence will always be hard to prove and it was not only a one-way street. Arun Kolatkar, legendary Indian English poet, who met Ginsberg when he had visited Bombay, did acknowledge the Beat poet’s influence on his work. Ginsberg was also quite punctilious in writing to his Indian contacts, including several writers, to solicit their support for Malay RC when he faced an obscenity trial over his poetry and manifestos, along with other Hungryalist writers.

Comments

Post a Comment